| Sheldon Mayer | |

|---|---|

|

File:Sheldon Mayer self-portrait.jpg Sheldon Mayer self-portrait | |

| Born |

April 1, 1917[1] New York |

| Died |

December 21, 1991 (aged 74) at his home in Copake, New York |

| Nationality | American |

| Area(s) | Writer, Penciller, Editor |

| Notable works |

Scribbly, Sugar and Spike, Three Mouseketeers, Black Orchid, Funny Stuff |

Sheldon Mayer (April 1, 1917 – December 21, 1991) was an American comic book writer, artist and editor. One of the earliest employees of Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson's National Allied Publications, Mayer produced almost all of his comics work for the company that would become known as DC Comics.

He is among those credited with rescuing the unsold Superman comic strip from the rejection pile, and should not be confused with fellow Golden Age comics professional Sheldon Moldoff.

Mayer was inducted into the comic book industry's Jack Kirby Hall of Fame in 1996 and the Will Eisner Comic Book Hall of Fame in 2000.

Early career

Mayer's career in the days before comic books was a diverse one. He worked as writer and artist on "scores of titles" for a juvenile audience circa 1932-33, before joining the Fleischer animation studios as an "opaquer" in 1934.[2]

He began working for National Allied Publications (Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson's initial company, later known as DC Comics) shortly after it was founded, in 1935, writing and drawing stories and "thus becoming one of the very first contributors [of original material] to comic books."[3]

Between 1936 and 1938, Mayer worked for Dell Comics, producing illustrations, house advertisements and covers for titles including Popular Comics, The Comics and The Funnies.[2] Also in 1936, he joined the McClure Syndicate "as an editor working for comics industry pioneer M.C. Gaines."[3] While working for the McClure syndicate, Mayer came across Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster's unsold Superman comics strip, which he "immediately fell in love with."[3] He recalled in a 1985 book that, "The syndicated press rejected it about fifteen times. I was singing [its] praises so much that in 1938 Gaines finally took the strip up to Harry Donenfeld, who was looking for original material to run in his new title, Action Comics,"[3] where the soon-to-be iconic character debuted as the lead feature of the first issue. Action Comics editor Vin Sullivan is also among those credited with discovering Superman. Mayer said,

I was crazy about Superman for the same reason I liked The Scarlet Pimpernel, Zorro, and The Desert Song. The mystery man and his alter ego are two distinct characters to be played off against each other. The Scarlet Pimpernel's alter ego was scared of the sight of blood, a hopeless dandy: no one would have suspected he was a hero. The same goes for Superman.[3]

All-American Comics

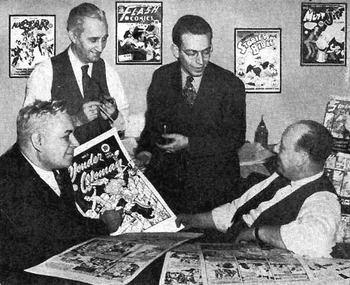

(Left to right) William Moulton Marston, H. G. Peter, Sheldon Mayer and Max Gaines in 1942.

In 1939, "Gaines left McClure to enter into a partnership with [National Periodical Publications]," and Mayer went with him, becoming the first editor of the All-American [Publications] line, then run as a separate entity from National/DC, publishers of Superman and Batman.[3] Mayer edited and participated in the creation of - among others - the Flash (in Flash Comics), Green Lantern, Hawkman, Wonder Woman and All-Star Comics, home to the Justice Society of America.[3]

Among his non-superhero work, Mayer assisted with lettering and logo creation on several All-American titles, and drew a number of covers for the "Mutt & Jeff" reprints appearing in the companies flagship title All-American Comics (1939–1958).[2] Having created the semi-autobiographical strip "Scribbly, the trials of a novice cartoonist,"[3] for Dell Comics in 1936, (where the character appeared in The Funnies #2-29 and Popular Comics #8-9[2]), Mayer moved Scribbly to All-American Publications in 1939. Soon after, the strip included the supporting character of "Ma" Hunkel, who would go on to become the Golden Age incarnation of the Red Tornado, with Mayer writing, penciling and inking the renamed Scribbly and the Red Tornado for All-American Comics between 1941 and 1944 (when All-American merged with National).[2]

Editorial retirement

Mayer retired from editing in 1948, "to devote himself full-time to cartooning" he began to write and draw a number of humor comics for National, including the features The Three Mouseketeers, "Leave It to Binky, a teenage humor book... [and] Sugar and Spike."[3] This last title proved to be one of Mayer's longest-lasting strips, starring two babies who could communicate in baby-talk that adults could not understand.[4] Mayer even signed the stories he drew, something rare at National Periodical Publications in the late 1950s when Sugar and Spike debuted.

In the 1970s, when failing eyesight limited his drawing ability, he continued to work for National/DC, contributing scripts to the companies horror and mystery magazines, including most notably House of Mystery (from c. 1970 for nearly 20 years[2]), as well as House of Secrets and Forbidden Tales of Dark Mansion.[2] With artist Tony DeZuniga, he co-created the "Black Orchid" feature which ran in Adventure Comics #428-430 in 1973.[5] Mayer wrote and drew several "Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer" treasuries[6] starting in 1972. These were published as Limited Collectors' Edition C-24, C-33, C-42, C-50[7] and All-New Collectors' Edition C-53, C-60.[8] Additionally, one digest format edition was published as The Best of DC #4 (March–April 1980).[9] In the 50th anniversary publication Fifty Who Made DC Great, Mayer is cited as still writing and drawing "for the company that first published his great discovery, Superman, forty-seven years ago."[3]

After successful cataract surgery, Mayer returned to drawing Sugar and Spike stories for the international market[10] and only a few have been reprinted in the United States. The American reprints appeared in the digest sized comics series The Best of DC #29, 41, 47, 58, 65, and 68. In 1992, Sugar and Spike #99 was published as part of the DC Silver Age Classics series;[11] this featured two previously unpublished stories by Mayer. DC writer and executive Paul Levitz has described Sugar and Spike as being "Mayer's most charming and enduring creation".[12]

DC attempted to license Sugar and Spike as a syndicated newspaper strip but was unsuccessful.[13] Sales on the "Sugar and Spike" issues of The Best of DC were strong enough that DC announced plans for a new ongoing series featuring the characters. The project was never launched for unknown reasons.[14]

References

- ↑ "United States Social Security Death Index," index, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.1.1/VSN8-T2H : accessed 13 Mar 2013), Sheldon Mayer, 21 December 1991.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Jerry Bails' "Who's Who of American Comic Books 1928-1999": Sheldon Mayer. Accessed July 27, 2008

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 Marx, Barry, Cavalieri, Joey and Hill, Thomas (w), Petruccio, Steven (a), Marx, Barry (ed). "Sheldon Mayer Superman Discovered" Fifty Who Made DC Great: 13 (1985), DC Comics

- ↑ Markstein, Don. Sugar and Spike. Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Archived from the original on December 13, 2011. Retrieved on December 13, 2011.

- ↑ McAvennie, Michael; Dolan, Hannah, ed. (2010). "1970s". DC Comics Year By Year A Visual Chronicle. Dorling Kindersley. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-7566-6742-9. "Very little was known about the Black Orchid, even after writer Sheldon Mayer and artist Tony DeZuniga presented her so-called "origin issue" in Adventure Comics."

- ↑ Sheldon Mayer. 'Don Markstein's Toonopedia'. Archived from the original on December 3, 2011. Retrieved on December 3, 2011.

- ↑ Limited Collectors' Edition #C-20, #C-24, #C-33, #C-42, and #C-50 at the Grand Comics Database

- ↑ All-New Collectors' Edition #C-53 and #C-60 at the Grand Comics Database

- ↑ The Best of DC #4 at the Grand Comics Database

- ↑ Markstein "Sheldon Mayer": "He continued to write and draw Sugar & Spike until 1971, when failing eyesight forced him to abandon cartooning...Mayer's sight was restored a few years later, and he went back to producing new Sugar & Spike stories. But the American comic book market was no longer able to support such a feature, so these were mostly published overseas."

- ↑ DC Silver Age Classics Sugar and Spike #99 (1992) at the Grand Comics Database

- ↑ Levitz, Paul (2010). 75 Years of DC Comics The Art of Modern Mythmaking. Taschen America. p. 64. ISBN 9783836519816.

- ↑ Wells, John (July 2012). "The Lost DC Kids Line". Back Issue (TwoMorrows Publishing) (57): 47. "Did you know that DC tried to sell Shelly Mayer's Sugar and Spike as a syndicated newspaper strip? [A] sample, ca. 1979-early 1980s was one of three DC concepts unsuccessfully pitched to papers."

- ↑ Wells p. 46-47: "In a 'Meanwhile' column in several Aug. 1984-dated titles...DC vice-president-executive director Dick Giordano tentatively announced Sugar and Spike #1 as appearing 'sometime this fall or early winter'...Ultimately, for reasons virtually no one recalls, DC quickly got cold feet on the project even as Marvel's Star Comics rolled out in 1985."

External links

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||